Tanker Trilogy III

1983

I will admit that I thought the term, “Tanker Trilogy” was catchy, so I guess this third KC-135 episode will have to be my last. This is not a story about an in-flight predicament, so if that is the extent of your curiosity maybe you should get on with your day. This one happened while sitting alert in the early 1980’s. We did not fly nor did we ever intend to. But if you are interested in learning about life in the now-defunct Strategic Air Command (SAC) on the front line of the now historic Cold War, I may be able to offer a glimpse. In addition, the weird combination of events taught me a lasting lesson on that particular day.

I was stationed at a standard SAC base. It had the standard 12,000-foot SAC runway with the standard SAC alert ramp on the end of it. This particular SAC base was called Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in Goldsboro, North Carolina. Other than being less frigid than the ones lining the Canadian border, it was just like the rest. The alert pad was a ramp area with room for eight Boeing airplanes, namely four B-52’s loaded with nuclear bombs and four KC-135’s carrying enough fuel to get the bombers to targets in the U.S.S.R. (Actually, I was never told where the targets were since only the bomber pilots had a need to know that highly classified information, but I think the U.S.S.R. would be a safe bet.) The parking spots were canted to minimize the first turn out of parking and onto the runway, which made the alert ramp look like a Christmas tree from above.

Next to the alert ramp was the alert facility, a multi-bed compound where eight crews would stay for a week, every third week. It looked like a prison, complete with razor-wire fencing to secure the nukes. Inside we had pool tables, a community television, and lots of telephones so we could talk with our families, still just like a prison. Nobody had cell phones back in those days, but we were issued “TAAN” radios that attached to our belt line which were able to receive voice messages sent from the command post such as, “FOR ALERT FORCE, FOR ALERT FORCE, KLAXON-KLAXON-KLAXON.” If we were to hear that, or the actual obnoxious blare of the klaxon horn, we were to drop what we were doing and immediately scramble to the flight line. It meant an automatic engine start with further instructions provided within a cryptic radio message. If we were being sent to war, the secret message would reveal it and we would launch. But that was never the case and we would never fly because the airplanes were loaded beyond peacetime weights. For exercise responses, it was always either a “mover” or just an engine start. A mover meant that as soon as we had the engines running, we would taxi to the runway, and then down the runway, and then taxi back to the alert facility. This was supposed to show the Russian spies that we could launch if we had to.

To be clear, the razor-wire fencing was to keep unauthorized people out, not to keep us in. Generally, we could leave the facility and go just about anywhere on the base. We could meet with our families at the BX or Officer’s club, for example, but were not allowed off base or to base housing. We could only travel in the alert vehicles, which were six-passenger pickup trucks. About every fifth telephone pole on the base had a speaker bolted to it ready to blare the klaxon signal. If the klaxon blew we had to drop what we were doing and scramble, no matter where we were. If we were away from the compound, this meant running to the alert vehicle and popping a flashing yellow light onto the roof, which we called the “Kojak” light because the popular TV detective named Kojak was always using one just like it as he raced through traffic. (Sadly, half of you will have to Google “Kojak.”) Routine base traffic was required to pull over if the klaxon was going, and speed limits did not apply to us. I have to admit, that part was kind of fun.

It was a nice day, the kind of day that might call for a family picnic, but instead all crews were required to go to the command post to study the classified EWO (Emergency War Order) procedures. Each crew had its own alert vehicle. I was the copilot on crew R-105, with the same three guys that had previously flown to Guam and Korea. Jonnie was the navigator, Teddy the boom operator, and the aircraft commander was Captain Trilogy. I named him that to point out his significant role in each of my most memorable stories without disparaging his real name. If he were guilty of anything on this day, it was being too mission oriented. We were all huddled around large command post tables studying the secret stuff that the Russians probably already knew. We read for the umpteenth time what to do if we were being trailed by a heat-seeking missile, what a poopy suit was, how to protect your eyes during a nuclear flash, and some other stuff that might actually still be classified. When it came to klaxon exercises, the wing commander probably got graded on our response time and he probably had some control over when a practice klaxon blew. He might have been stacking the deck by requiring us to be at the command post because the driving route to the airplanes would be via the flight line, away from civilian traffic. If he needed a good grade that day, he was denied, and crew R-105 was central to why.

You probably figured out what happened next.

“FOR ALERT FORCE, FOR ALERT FORCE, KLAXON-KLAXON-KLAXON.”

It was probably the first time I had received the transmission while watching the guy who was transmitting it, because that was the job of the people assigned to the command post. With the push of a button, he had all the klaxons throughout the base blaring, as well.

BAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA!

We pushed ourselves away from the table and ran out to our assigned alert vehicles. I am pretty sure the nav or boom drove that day, not that it mattered. Whoever was riding shotgun pulled out the Kojak light and slammed it onto the roof (you would have to watch the show to understand why we liked that part so much) since the driving route was right down the taxiway, and we could drive speeds unheard of anywhere else on the base. We were probably doing 70-80 miles per hour as we raced with the other seven alert vehicles to the alert pad.

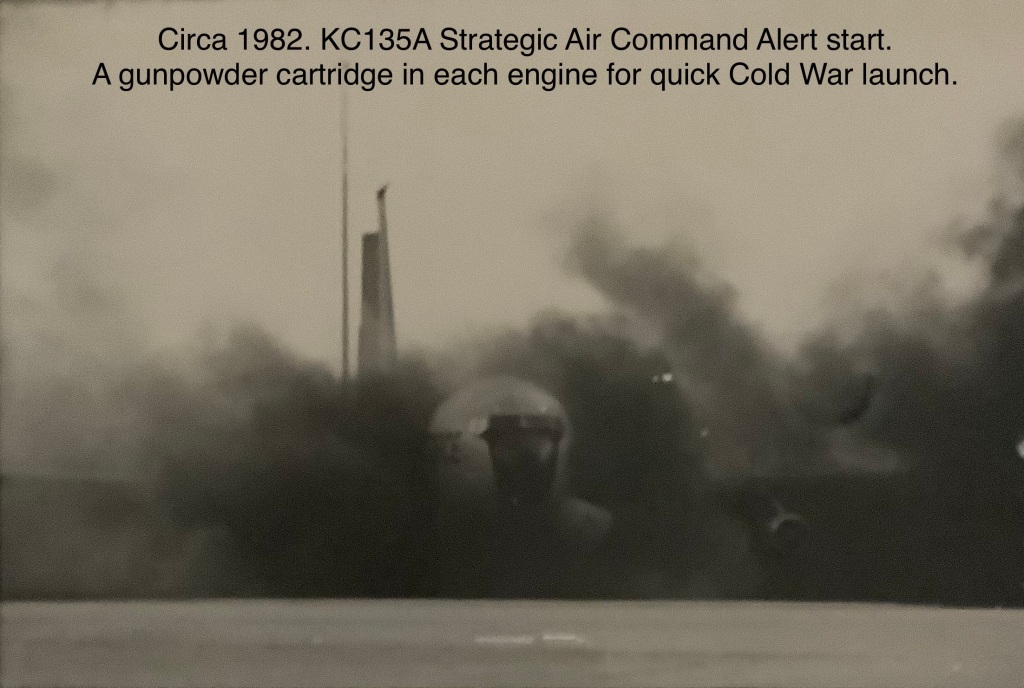

Arriving at our airplane, we jumped out and ran up the vertical ladder entry door. Captain Trilogy and I fired up all four engines simultaneously while the boom operator pulled up the ladder and closed the door. The next time you fly commercially, you will notice that the pilots turn off the air conditioning when they start the engines. That pneumatic air is diverted to the starter because jet engines are normally started with compressed air. But on alert, the needed pressure was supplied with gun powder. Each engine had a can of it mounted adjacent to the starter. The size of the can reminded me of the canned vegetables at Sam’s Club. With gun powder, we could gang-load the start switches and have all four engines running in about a minute. Captain Trilogy started the left two and I started the right two. Meanwhile, we could all hear the coded message coming across the radio. The nav was dutifully copying and decoding the cryptic message. A typical message would contain over thirty characters but we only heard the first six, which we knew as the “preamble.”

“Message follows: Alpha November Zulu Tango Tango Kilo.”

“Nav, is it a mover?” Captain Trilogy asked as our four engines came to life.

“Well, it’s a mover, but I only have the preamble,” was the reply. For some reason, they stopped transmitting the rest of the message, but he could tell from the first six characters that it was a peacetime mover. Meanwhile, another crew requested a repeat of the message, but was told by the command post to stand by. The following discourse ensued.

Captain Trilogy: “Well it’s a mover then, right?”

Nav: “Well yeah, it’s a mover, but I don’t have the whole message.”

Captain Trilogy: “Well if it’s a mover, I’m gonna go.”

I rapped him on the shoulder and pointed out emphatically, “He says he doesn’t have the whole message!”

He replied, “I see the bombers moving and I’m gonna go. Clear left.” He looked toward his left wingtip out of habit to look for things he might hit. I could not think of anything else to say at this point except, “Clear right.” There was one thing that would have stopped him, but I didn’t think of it. The situation was catching several people by surprise simultaneously.

We were rounding the corner behind a bomber and exiting the alert pad when the command post began transmitting the entire message.

“Message follows: Split Launch. Alpha November Zulu Tango Tango Kilo Delta Bravo Romeo Quebec Whiskey Uniform November Mike Kilo Juliet…”

This time the complete message was transmitted.

The second I heard the term, “Split Launch,” I literally saw a question mark pop into the air above Captain Trilogy’s head, followed immediately by a light bulb. I am sure he saw the same above my head. “Split Launch” was the only thing I could have said to stop him from moving the airplane. He should have given more consideration to my sense that something was not right, but I learned an important lesson that day. While it is important to speak up when something doesn’t seem right, you must put your finger on the issue and say it out loud if you really want to affect the outcome.

SAC members tended to reduce a klaxon to either a mover or not a mover. We were always required to start engines, and the third choice of actually launching was unprecedented and unlikely, if not unthinkable. True for the bombers, but for the tankers there was actually another choice filed in our minds as a footnote. “Split Launch” was the one time we didn’t move, even if the message said it was a mover. Under ordinary circumstances, we would have been told of the split launch status in advance so we could sort out the implications in our minds. But we did not get that luxury on this day. In fact, everything about the morning would have ruled out the split launch status. Under those conditions, specifically the winds, we would not have been allowed to be at the command post in the first place. So even without more detail about split launch, you should already see that the guys in the command post found themselves in a pickle when they took a closer look at the winds. They were under orders to blow the klaxon, but they had the crews out of position for the conditions. The pause in the message happened when they realized their mistake and tried to recover from their own quagmire. To transmit, “Split Launch,” would shed light on one mistake, and to ignore the conditions requiring split launch would represent another mistake. They had not noticed the conditions creeping up.

As you probably know, a headwind is always better for takeoff because the airplane achieves flying airspeed sooner. The B-52’s, with their eight engines, could handle a significant tailwind, but most tailwinds would require the KC-135’s to taxi almost three miles to the opposite end of the runway and take off the other way. The command post was supposed to communicate split launch status whenever conditions were like that. This would essentially restrict the tanker guys to the alert facility. This meant no bowling with the wife and kids, or grocery shopping, or library, or doctor’s appointments or a number of other liberties. We could neither visit the squadron nor the command post. We had to stay close to the airplanes. If it was war, the crews could sort out the opposite direction takeoff sequence on the radio, but a peacetime “mover” would result in a gridlock on the runway and taxiways because of opposite direction traffic. So, if the peacetime exercise was a “mover” during split launch conditions, the bombers would taxi and the tankers would not, except for R-105 on that day.

So, there we were on that day, second or third in the line of aircraft heading toward the runway. By now everybody had heard the complete message and knew we should not have moved. I asked on the radio where they wanted us to go and I saw the microphone moving as we passed the wing commander’s white-top sedan. “Just follow the bombers,” was the reply with a heavy intonation. So, we followed them down the runway and then back to the alert pad where a tow vehicle pushed us back into our spot. Except for the dirty task of cleaning out the start canisters, which fell to the boom operator, the rest of us were free to go into the alert facility.

I was soon cornered by a Major asking me, “What were you thinking?” As if the now obvious was always obvious. I relayed what happened to him just as I did to you, which could be interpreted as throwing Captain Trilogy under the bus, or not if you consider that we had successfully demonstrated our readiness despite the mistakes at higher levels.

It is easy to conclude that sometimes it is not good enough to say, “This does not feel right.” I learned the importance of putting your finger on the reason and articulating it loudly in order to redirect another crew member’s mindset. That was the important lesson to me on that day. While it might not sound easy to extract from your mind the thing that you are not thinking of, at least I know to force my mind to increase its processing speed in that pursuit. And I think it has served me well in the years since.